[I’m currently studying MLitt Comic Studies at Dundee University. The course involves looking critically at comics and their history. This is the first in a series of journals I’m posting from the course.]

MARK CURRIE ARGUES THAT METAFICTION IS “A BORDERLINE DISCOURSE, A KIND OF WRITING WHICH PLACES ITSELF ON THE BORDER BETWEEN FICTION AND CRITICISM, WHICH TAKES THE BORDER AS ITS SUBJECT”. DISCUSS.

Mark Currie defines metafiction as narratives that are “somehow about fiction itself”, using “self-consciousness, self-awareness, self-knowledge [and] ironic self-distance.”1 Most postmodern literary theory puts distance between the author and criticism of the work1 , or as Roland Barthes describes it: “the text is henceforth made and read in such a way that at all its levels the author is absent”.2 Metafiction, however, shows the authors’ hand by engaging in a kind of self-referential critique that can take a number of forms.

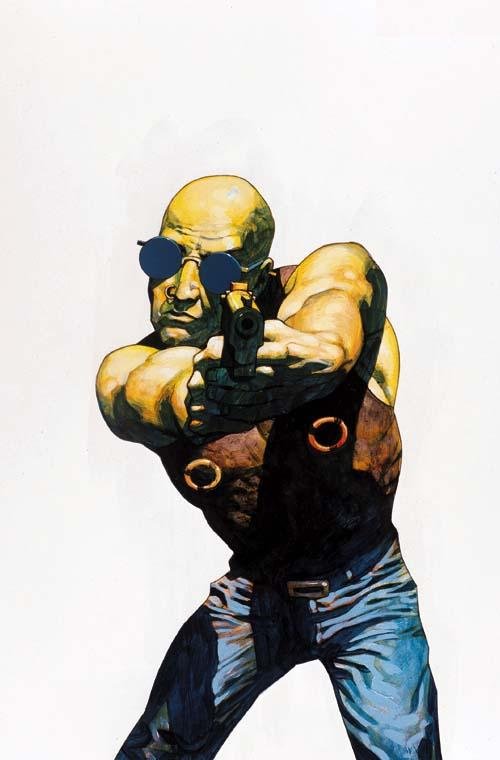

In Flex Mentallo Grant Morrison “dramatises the boundary between fiction and criticism” by producing a work that is at once semi-autobiographical and a critique of the superhero genre.1

Morrison explores the nature of the boundary between comic and reader, with the author acting as a kind of psychopomp, or spirit guide, between the two realms. In The Invisibles, he first plays with the idea of character-as-surrogate, fashioning King Mob as an avatar for himself (with the later suggestion that fictional events began to have a real-world impact on Morrison).3

By the time of Flex Mentallo, Morrison was using the author-surrogate as a way to critique the genre and write a work of semi-autobiographical fiction. Wally Sage experiences a breakdown in which the lines between fact and fiction are blurred, and he finds himself both disintegrating as a personality and integrating with the comic world of Flex.4

We know that it is an autobiographical work because Morrison leaves clues, such as in issue 3 page 9, where Wally says the following:

“Was I telling you about those political bookshops my Dad used to take me to? What was I saying?… Those terrible ban-the-bombzines; when you’re a kid they look just like comics at first but they’re not. It’s all screaming Hiroshima faces, burning cities. I used to imagine God was a skeleton and the thunder was the sound of his big, black iron train. War, apocalypse…”4

Morrison talks at length about these ‘zines in his later autobiography Supergods.5 Wally acts as a vehicle for Morrison to reveal something of himself, but also to deliver a critique of comics, and of the superhero genre. As a kid, he thought those ban-the-bomb ‘zines were comics, but in reality, comics were escapist – they didn’t reflect the harsh reality of growing up during the Cold War.

Even in the so-called ‘Dark Age’ of the medium, superhero comics weren’t so much engaging in a critical analysis of reality or reflecting the world in which the were created. The sex and violence that marked the era were still forms of escapism.

In Flex, Morrison not only parodies this era but engages in a critical appraisal of it, as well as superhero comics in general, by relating them to the dissolution Wally experiences. Grown-up Wally might just find himself in such a dark place since he, like many childhood comic fans, abandoned them as immature. In doing do, he has lost the magical/imaginative side of existence and is left in a nihilistic and suicidal void.

Flex, then, is both a critique of and paean to the world of comics and their importance to the author and the readers is hammered home through the use of metafiction.

Far from being an invisible actor in the work, metafiction such as this reveals the author to be engaged in exploring the boundaries between fiction and criticism, fact and fiction.

References

1 Mark Currie, ‘Introduction’, in Metafiction, ed. by Mark Currie (Essex: Longman Group Limited, 1995), pp. 1-18.

2 Roland Barthes, ‘The Death of the Author’, Image Music Text (1977), 6.

3 Grant Morrison, The Invisibles Omnibus (New York: DC Comics, 2012).

4 ———, Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery – the Deluxe Edition (New York: DC Comics, 2012).

5 ———, Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero (London: Vintage Books, 2012).